"Science has always been a bit shit"

It evolved that way

The last few months in science reform has seen two prominent claims that research is like an evolutionary ecosystem by Richard McElreath, and by Thomas Morgan at the University of Arizona. Evolution is an excellent metaphor, made famous by McElreath’s paper The Natural Selection of Bad Science (2016) and even more so by the phrase “publish or perish.”

The problem with invoking evolution is that it’s hard to claim an evolved system where the strong cheat can be fixed with more rewards, ones the strong aren’t going to get ahold of.

The current plan for replacing “publish or perish” is “don’t publish as much but we’ll make sure you live, we promise!” It isn’t going to work. We need “publish poorly and perish” like every ecosystem and in fact, profession.

Richard McElreath, who did not respond to a request for comment, is a legendary Bayesian author. The rewards in his piece are many, such as the 18th century reference to careerist “bread scientists,” and McElreath’s general disagreement with open science tisk-tisking its way to a better system. Dr. McElreath is an exceptional educator and “The Natural Selection of Bad Science” is one of the best papers in metascience.

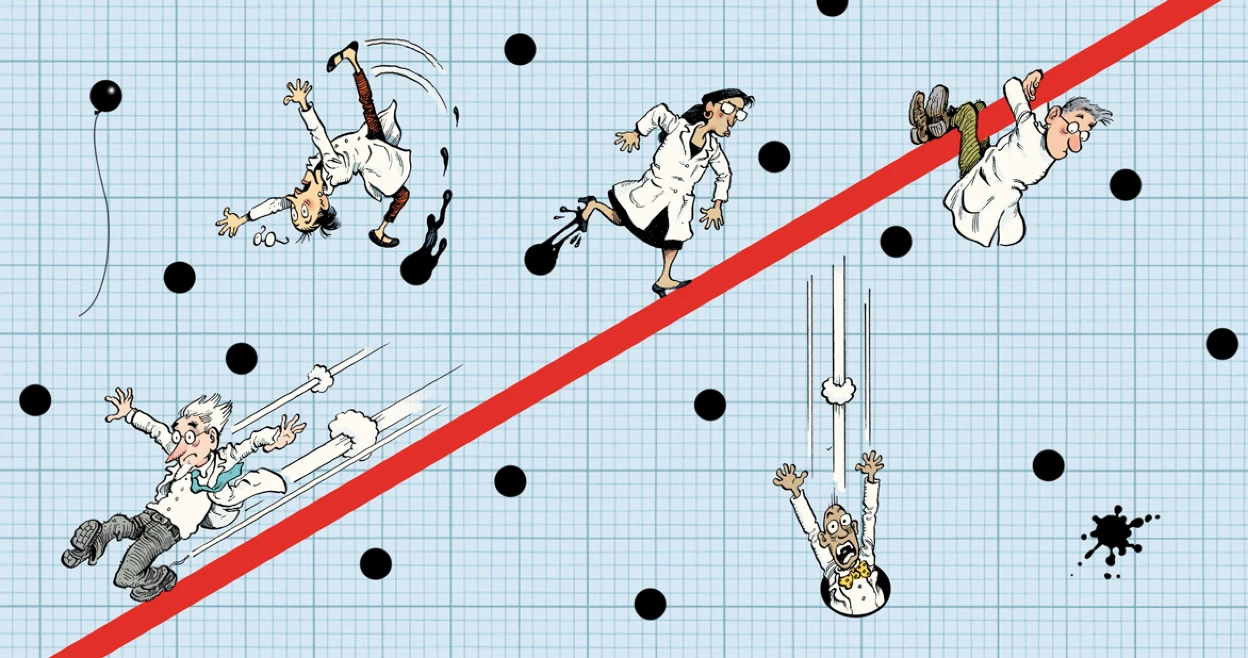

In the 2010s, as psychologists talked about subconscious, or forgetful p-hacking, McElreath and his co-author Paul Smaldino got at the unfortunate truth that science is an ecosystem like any other where the strong survive, sometimes for the wrong reasons.

Ten years later, McElreath accepts the consequences of his own paper by again comparing working scientists to an evolutionary system. So he has no excuse for making the same mistake others have made by advocating for new tweaks and tunes that will fix it using academia’s own meager appetite for reform.

Academia’s appetite for reform is truly minuscule. Science is a system that is indeed “a bit shit,” as he says. McElreath is a Bayesian, so its major reform, yet to be realized, should have swept through around 1763.

Foxes and bunnies

In short, McElreath thinks many of the standard reforms won’t work, and proposes some of his own, which are, for instance, training in data management and statistical modeling. He correctly points out that other high-level officials in science like himself have enjoyed evolutionary success in a bad system and so may be the worst instead of the best. We’ve seen many instances of this. Gino at Harvard, Tessier-Lavigne at Stanford, Wansink at USDA, Masliah at NIH.

McElreath’s error is ubiquitous. Despite having simulated the effects of labs propagating bad methods and “dying” if they don’t, the real horror is the honest researchers not knowing data management while dying. In other words, instead of the more obvious and tested system of checks and balances, of “foxes and rabbits” in evolutionary terms, we can breed the bunnies to jump off a high cliff once they’re not serving the ecosystem anymore. Evolution doesn’t work that way.

It certainly hasn’t worked that way in science. As food (discovery) becomes scarce, scientists feast on p-hacking and base rate neglect. This is obvious. As McElreath says, there are things everyone already knows. I suspect this is one of them.

The fact is that bunnies don’t stop eating even when faced with ecological collapse. Scientists don’t stop publishing and methods don’t stop propagating. Survival is how they got here.

We love these particular bunnies. They’re brilliant and kind. However, when it’s time for their careers to suffer, they do untold violence against the scientific record and thereby society to save their own skin. As almost anyone would. Their skills in data management and statistical modeling don’t matter.

No excuse is necessary to say that researchers who use poor methods shouldn’t have careers, but in case this seems cruel, consider that publish or perish is a silly metaphor. Science — as scientists have endlessly pointed out — is actual life-or-death for the rest of us.

The foxes this site has advocated for are independent post-publication reviewers separate from academia. They may not be as educated as the bunnies but they know when a paper should perish. It is often obvious, held back only by the researcher’s indomitable will to survive.

I believe, as McElreath does, that this system will arise with or without our help and it already has. In the United States, the foxes are now, by law, political appointees and the ecosystem is going through collapse.

The Natural Selection of Bad Science must be read, and we have to accept what it means. The fact that McElreath himself does not is the perfect illustration of academic reform.