The cherry on top

Replication crisis ironies continue

If this blog has a thesis, it is that research is troubled and addressing it with half-measures may make things worse. Science may boot out or exhaust the reformers. The reformers may be “captured” the way that industries capture their regulators. This is because the incentives in science are strong. We assumed in the early days of the replication crisis that the incentives were strong, but we had to estimate how strong. After 20 years, there’s enough evidence to say that we underestimated.

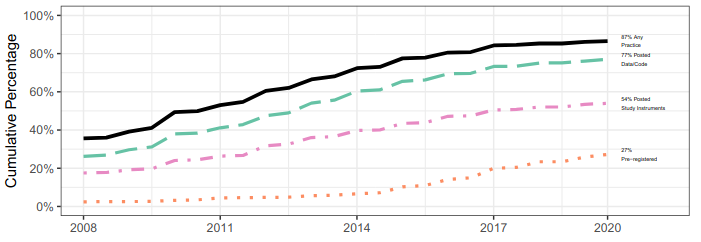

Along the same lines, metascience, or research on research, has at times not been impartial when evaluating itself. Reformers tend to highlight and sometimes exaggerate the success of interventions. “Critical metascientists” tend to say there wasn’t a replication crisis in the first place using the most favorable statistics. (We know these statistics vary dramatically.) For instance, the use of “cumulative percentage” in adoption of good science practices. The chart below on year of first use of open science practices makes it look like a revolution is happening (from Ferguson et al., 2023).

One recent paper implies that the revolution not only happened, it's working. The paper's plotting technique is to truncate, not accumulate, but the visual effect is the same.

Unfortunately, this paper gives reformers and critics something to agree on. In one sense, some kind of intervention must have worked. In another, science, specifically psychology, is healing on its own. Not only that, but it's healing before we see a need to test the other fields.

The paper, “One Decade Into the Replication Crisis, How Have Psychological Results Changed?,” has been well-covered and criticized on small blogs and social media, and yet it was written up in Science with a small whiff of skepticism.

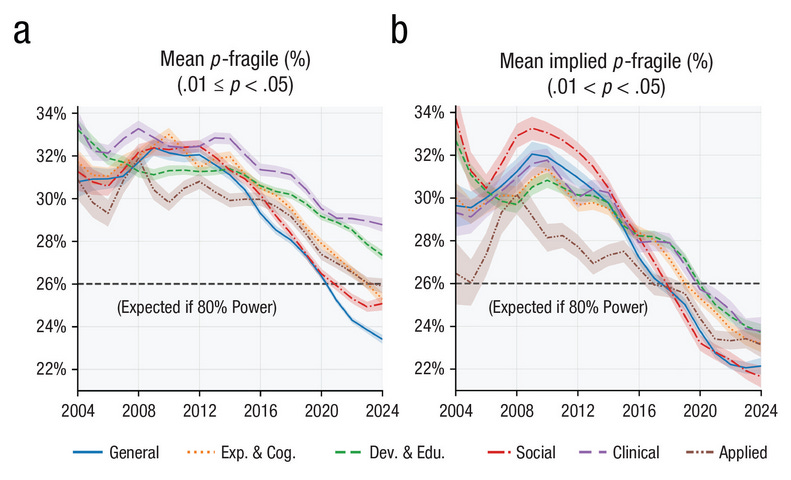

The first criticism I will add to the pile-on is that the paper doesn't mention p-hacking. (0.01, 0.05) p-values are simply “weak” and < .01 ones are “strong.” The weak in general are suspect. That there are still a lot of them published suggests “issues eliminating the most problematic research.” (So much for publishing null results with even higher p-values.)

The distribution of p-values the author collected and analyzed is called a p-curve and it primarily measures p-hacking. This distribution doesn’t appear in the paper or supplement. The analysis reveals only what intervals on the curve have changed compared to one another, and they’re the wrong intervals.

The original p-curve paper is cited. So the author is aware of why p-curves are useful: more values than expected just under the traditional threshold of 0.05 may indicate p-hacking. Even better if you can see a corresponding trough just greater than 0.05.

It's hard to know where this “hump” in the distribution will occur other than the upper limit should be the publication threshold of 0.05. However, we should suspect for empirical and common-sense reasons that the lower limit the author used, 0.01, is exactly the wrong one.

This is because, if anything, 0.01 is another upper limit p-hackers may want to get underneath. The problem is compounded by the fact that hacked p-values make the >= 0.01 bin smaller and the < 0.01 bin bigger.

The original authors of the p-curve paper called this “ambitious” p-hacking.

Almost any lower limit would be better than another number researchers use as a target. But we also have some good empirical guesses as to what it should be. The lower end of the “hump,” measured from 50,000 tests in economics papers is around 0.025. Others have used 0.041-0.049. There’s no way of knowing a priori where the lower end of the interval should be, however 0.01 is not a good guess. A p-curve would have helped.

In other words, fewer “fragile” p-values measured 0.01-0.05 compared to 0-0.01 may mean there's more ambitious p-hacking than there used to be.

The author doesn’t justify the choice of lower bound and although he does a lot of analysis to test the robustness of the finding, there’s no test of the most obviously-arbitrary choice in the paper. Neither is this choice preregistered.

The second criticism is, as others have pointed out, there are lots of reasons p-values might be going down. Modest changes in other factors may have led to the modest change observed. Reasons tended to be neutral or positive like an increase in sample sizes.

These are not all of the reasons. The most obvious one is p-hacking. Additionally:

1. Computing power has increased, which makes p-hacking and selective reporting in general faster and cheaper.

2. Hypotheses may be getting safer.

3. We are now suspicious of “fragile” p-values because of Bayesian and flexibility criticisms starting in the early 2010s. The fragile interval may simply have become less desirable. This is supported by the paper’s own conclusion that “contemporary articles reporting strong p values tend to find publication in more esteemed journals and receive more citations.”

One of the responses to the original p-curve paper is that biased analysis choices aren't limited to nudging a p-value under 0.05. They may leap over that interval and cluster at very low p-values.

It should also be suspicious that we're seeing what's interpreted as improvement in the most dubious and often-criticized metric, p-value, and no improvement in others, including the core metrics of self-correction and the replication rate. This paper is carefully selecting what to show from its p-curve distribution, and carefully avoiding the other signals from metascience from the same time-period.

Science takes this a step further, putting the “big win” quote in the headline, and supposing that the paper may mean there’s less cherry-picking in psychology.

It’s not all bad. We should be grateful this work was done, reveals something, even if it wasn’t what was intended, and the data and code are available. However, the paper follows a string of replication crisis ironies: the study of dishonesty that was dishonest, the disinformation researcher spreading disinformation, and the preregistration paper that wasn't preregistered. The study that found less cherry-picking was cherry-picked.

The author isn’t shy about how he’d like his results to be used. He writes that some laypeople have heard of recent failures to replicate psychological studies (oh no!) and “Ideally, the results here can serve as a springboard to communicate the rigor in much of contemporary psychology.”