COVID origin may be simple

Each market is safe

Summary of key points:

SARS emerged in 2002 from a wet market. This is a common argument for a zoonotic origin in 2019.

There are over 30,000 wet markets in China. Individual markets are very safe.

The market hypothesis rests on the safety of an individual market.

It is wrong to confuse the safety of all 30,000 markets together with the safety of an individual market.

The proximity of the lab and the market means we need to compare individual market safety to individual lab safety.

We don’t know how safe individual labs are but we only need a rough guess for the comparison. One way to do this is to consider 30,000 coronavirus labs in China.

Keeping with simplicity, all of these points will be translated into decks of cards and other things we understand well.

A brief philosophical justification

It is a well-accepted truth in science that method is what matters. We cannot evaluate research by its result. Otherwise, we may come to any conclusion we like. Suppose we want to conclude that the Earth is flat. All we need to do is accept the results of those who claim it is flat and reject others. This principle doesn’t simply work because we strongly believe the world is round. It works because evidence is like reality. Ignoring it doesn’t make it go away.

So ignoring evidence is a sort of epistemic sin. You shouldn’t do it.

Of course, there is such a thing as bad methods and we are allowed to doubt findings on the basis of methods. The problem with doubting methods on and on, however, is we are faced with an infinite regress. The methods are background assumptions that rest on their own background assumptions going back as far as you like (Bayes, Duhem-Quine, Hume). The infinite regress of doubt is real, but we can’t retreat to it in order to win. It’s always there, and strategic retreat is like any rhetorical device that always works. That which proves anything proves nothing.

This retreat-or-ignore phenomenon is a good description of the COVID origin debate. The simple argument is ignored and the experts have “kicked the debate into the long grass” of complexity and methodological doubt. Experts claim it is complex and so we should trust the 20% chance estimate from experts instead of the roughly 64% estimate from non-experts. This is the assumption we’re going to question here. What if the answer is simpler than experts say?

The Lab Leak Hypothesis

An estimate accepted on both sides of the debate is that experts put the chance of a lab leak at 20%, on average. 20% is a large chance and it’s an epistemic sin to ignore it. It’s hard to imagine some conventional wisdom pre-pandemic that we should disregard future conspiracy theories that have a 20% chance of being true.

COVID origin may be simple. If it is, the common sense argument about proximity to a coronavirus lab may be sufficient to direct the debate. This argument can be translated into math and the math is simple and one-sided. The math is one-sided because there are many wet markets in China.

Each wet market is safe

We find this unintuitive in the West. Each wet market is very safe. Just like airplanes that do crash in aggregate, individual airplanes are safe. It takes the force of millions of flights to make a single crash. Using the force of all those flights together to convince you to be scared is something your brain does in flight but nonetheless you are safe. You’re only on one plane and there are many others.

It took the force of 30,000 wet markets in China to create one pandemic in 2002 (SARS).1 Even if we grant the 2019 pandemic to zoonosis, that’s one pandemic every 17 years for 30,000 markets. If there were only two markets in China and they led to a pandemic in 2002, and another pandemic emerged next to one of them 17 years later, it would be justifiable to say it came from the market.

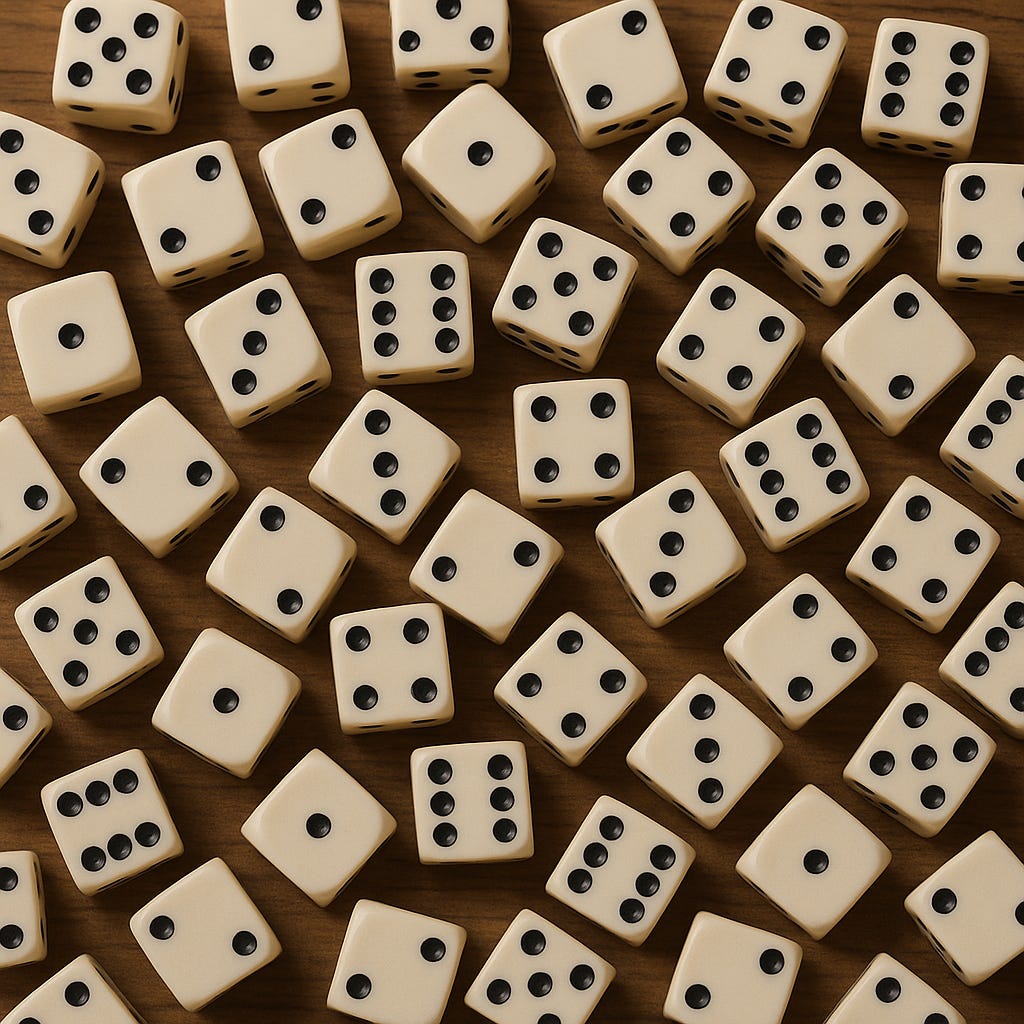

Confusing individual and aggregate probabilities is obviously wrong. Roll 100 dice. One of them is almost always a 4. This is a rate of “almost every time.”

“Almost every time” is not the rate of 4s on a single die. Rolling a single die will only give a 4 every few throws.

Even if the statistics are not clear, you can’t get a 4 almost every time and a 5 almost every time, and a 6 and so on using one die. You can get all those numbers easily with 100 dice. Similarly, you can’t get mostly heads and mostly tails with one coin.

Some other obviously false statements that rely on the same confusion:

Someone in the casino wins $100,000 every day. If I try this slot machine for a full day, I will likely win $100,000.

One plane crashes every few years. Planes are unsafe.

1,000 people are throwing a dart at a giant dart board. Closest to the center wins. Player 5 has a good chance of winning because everyone gets one dart: Player 5 has the same chance as the winner!

All of these statements can be corrected by dividing by the number of things working together:

If I try this slot machine for a full day, I will have about a 1/(the number of slot machines) chance of winning $100,000.

One plane crashes every few years. This plane has a 1/(number of flights per year × number of years) chance of crashing.

Player 5 has a 1 in 1,000 chance of winning.

The logic of proximity using decks of cards

The logic of proximity is intuitive and we use it all the time. If you turn your back to an elevator, then hear a ding, you don't assume it was an elevator five miles away.

Shuffling two decks together

Take two decks of cards with different colored backs. Put 3 jokers in the red deck, and 1 joker in the green deck. Shuffle them together. Then draw cards without looking at the back until you draw a joker. Which deck is more likely the source? Obviously, red.

Now suppose that there were a bunch of decks on the table that you didn’t choose from. Does it matter that there were other decks? No, because you didn’t choose from those decks.

This sounds too simple for something unintuitive but it bears repeating. You didn’t choose from those decks. You can’t hear an elevator five miles away.

Let’s put an even finer point on this. Use the cards to represent a map of China. Take 25 green decks, each with one joker, and arrange them around a table. Draw one card from each. You’ll draw a joker about every other round of draws from all decks. That’s the aggregate rate of pandemics from markets. It takes the force of all the decks together to make a rate that high.

Proximal decks

Now start with 25 green decks. Take a green deck (1 joker) and a red deck (3 jokers). Instead of shuffling them together, put them close to each other. Draw from them with your eyes closed such that you can’t tell which one you’re drawing from each time. Suppose you draw a joker. Which deck did it more likely come from? The red deck, same as before. Knowing the number of jokers in the two decks is sufficient for answering this question.

Adding an adversary

Studies have shown that adding an adversary makes unintuitive math problems easier. Adding an adversary frames the problem as “cheating detection.”

Suppose you’re playing a game in which your opponent gets a point when a joker is drawn from a green deck and you get a point when it comes from a red deck. Take the same scenario with the green decks representing markets, and one red deck close to a green deck.

Suppose you draw from the two decks with your eyes closed and get a joker. Your opponent snatches it and tosses it into the discard pile before you can look at the back. He says the joker probably came from a green deck and so he gets a point. When you draw from all the green decks at once, you get a joker every other time; if you draw from the one red deck, you hardly ever get a joker. So the joker probably came from green.

You say that you weren’t drawing from all the decks.

Nonetheless, he goes on. The rate is much higher using all his green decks together than it is from your one red deck. He has more jokers in total. You reply that it wouldn’t matter if he had a million decks and a million jokers, if in fact, all the physical universe were packed with green decks end to end. You didn’t draw from those decks.

Estimating individual lab safety

We don’t know how fast labs produce pandemic-level viruses. A pandemic-level virus has never come from a lab. This could mean that pandemic-level viruses never come from labs, or the rate could be 1 pandemic every 100 years. As with other background assumptions, we can’t choose the estimate based on personal stakes.

We also can’t say it’s likely zero because it’s never happened. Experts on both sides of the debate agree that it is technically possible that COVID came from the lab.

We can guess, though, because we don’t need to know exactly how safe individual labs are. We only need to know how they compare to individual markets. One simple way to do this is to imagine 30,000 labs in China.

Does 30,000 labs start to approach the danger of 30,000 markets? 30,000 is a lot of labs. But even then, equal comfort with 30,000 labs only means you think the lab and the market are equally likely to be the source. In order to ignore the lab, you would need to feel safe despite the existence of many more than 30,000 labs. And you would need many many more than that to get to dismissable conspiracy theory territory.

So the belief that lab leak is a dismissable conspiracy theory requires the belief that many tens of thousands of coronavirus labs the size of the Wuhan Institute of Virology in China are equally dangerous to the current status quo. To put this in perspective, building 3,000 WIVs would only make us about 10% more worried about pandemics coming out of China.

One easy rebuttal to the many markets argument is that some human activities that seem unsafe are safe like flying in a plane. Having many labs in China could be like having many airports. This is true. Labs could be something we’re able to do safely. But consider how insensitive we have to be to not figure out if it is like airplanes. It means we’re okay with one lab and about equally okay with a lab every few miles.

Conclusion

Aggregate probabilities can be unintuitive. We’ve probably all heard casino schemes like the one above, and everyone has had doubts flying.

The safety of wet markets can also be unintuitive.

Combined — and with the emphatic assurances of many experts — COVID origin is more fraught than debates about drawing cards or getting on an airplane, but the naive probabilities are the same. Even if you don’t agree that they point towards a lab origin, they at least demand a better estimate of the missing quantity: individual lab safety. Even very low (safe) probability points at lab origin.

The assumption the many markets argument rests on is that COVID origin is simple. It may not be. It is worth considering that COVID origin is simple, though, because the stakes are high and because simple arguments are easy to understand. It at least won’t take long.

The estimate often used is 40,000. 30,000 was chosen for the sake of argument and it is the lowest estimate in the same Statista analysis. The argument is not very sensitive to the number of markets, and low numbers start to conflict with the Chinese Academy of Engineering estimate, which puts the size of the wild animal trade used for food at $19 billion. 10,000 markets, for instance, makes the case and it would mean each market accounts for $1.9 million in trade per year.