One of the most dangerous ideas in science was a misunderstanding

It's only getting more popular

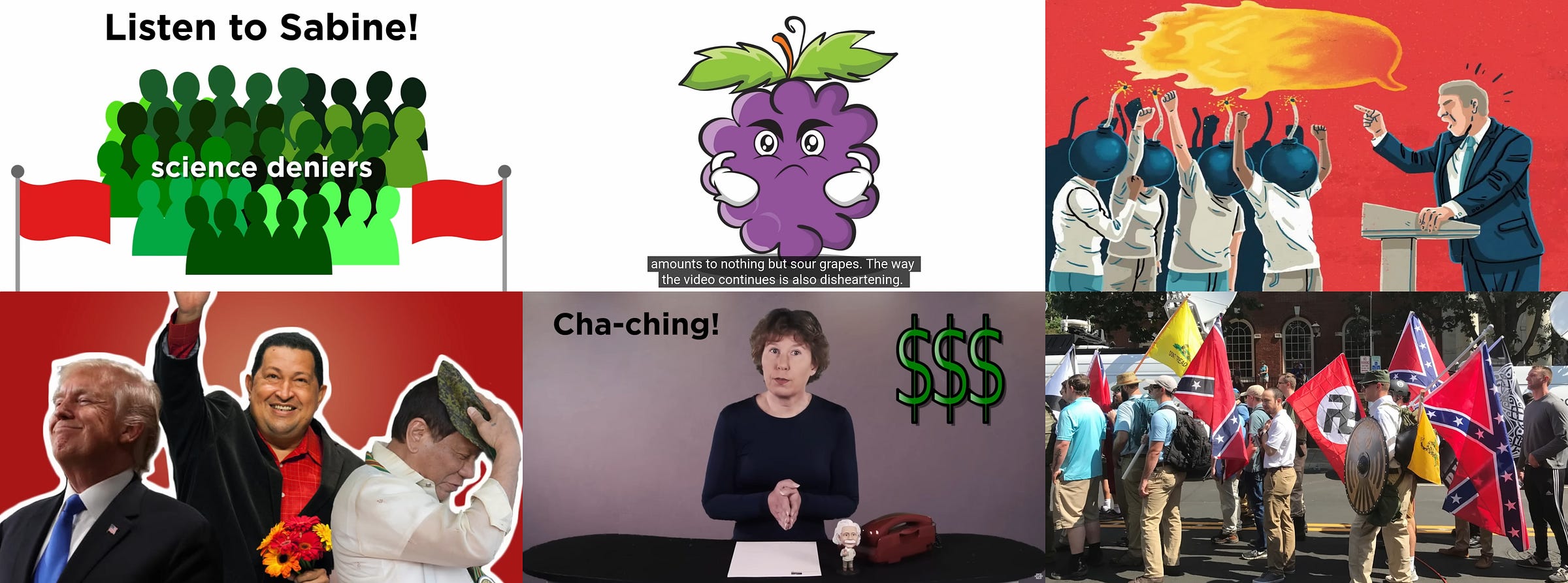

The battle for the soul of physics follows a familiar pattern: the winners versus losers. The early replication crisis was winners versus losers too. Established scientists called those who believed in the crisis “methodological terrorists” and “second-stringers.” Today, winner physicists say that critics are “poisoning society,” and claim to be “punching down.” The winners can’t help letting you know they’re winners.

These physics defenders have lined up against critics who say certain non-empirical theories are nonsense. The defenders claim 1) that these theories are not all of physics, 2) not a lot of physics, and 3) even if they were, it’s fine because the theories might be true.

All of these responses focus on the theories, not the glaring issue of empiricism physicists have been elaborately underscoring for decades.

In 2015, string theorists turned explicitly against evidence. They brought out an intellectual superweapon, something that would not only save their theory but all theories. By the time the philosopher behind this admitted physicists may have misunderstood, the genie was out of the bottle.

Despite this obvious danger to the scientific bedrock, empiricism gets lost in squabbles over rhetoric: should Physics World have said “cult” or “cult-like?” Should they have put “obedient idiots” in quotes?1 On YouTube, Professor Dave, a science communicator with 4 million followers, escalated the fight well beyond his “poisoning society” line to the idea that we need “warriors for science” in his critique of Sabine Hossenfelder’s frequent use of “science is broken” and “I don’t trust scientists.”

Hossenfelder’s rhetoric is no doubt blunt, but she’s made clear that the issue is a lack of attention to empiricism. Before she started, as she admits, “trying to annoy physics into doing something,” she wrote the article, the paper, the book, spoke at the conference, and did boring videos that few watched. The fact is that showing that something is non-empirical in a paper doesn’t enlist every physicist on Earth to your cause, even though it should. It gets a few dozen citations. What she gets now are longer and longer responses that avoid the issue.

Here is the simplest form of the argument that can’t be misunderstood: non-empiricism is an intellectual superweapon. It gives the possessor extraordinary and unearned powers of false discovery. Defending science from it is exhausting because many would like to possess it, and it quickly gets turned on you.

The debate has become so detached it seems to be about denying the superweapon exists, let alone who’s using it. Professor Dave isn’t telling the troops what they’re fighting for. What he says over and over, in a style that can only be called “relentless,” is that defending academia is defending empiricism.

The Misunderstanding

In 2015, physicist and philosopher of science Richard Dawid published what would become his most cited paper. It rests on the definition of the word “confirmation,” which he has rewritten so it looks like a finding:

“If one measures confirmation in terms of increase in degrees of belief, as Bayesians typically do, T is confirmed by E whenever P(T|E) > P(T). Throughout the paper, we use this inequality as a criterion for when a piece of evidence confirms a hypothesis.”

Dawid doesn’t cite anyone here because there’s no one to cite. The Bayesian epistemologists he cites elsewhere use different definitions and 1. make clear that “confirms” means “is evidence for” not the usual definition “verify” and 2. use “iff” instead of “whenever”:

The use of “confirms” is not a finding. It is the definition of a confusing philosophical term. What he’s doing is a sort of scientific arbitrage, importing a trivial term from philosophy into a field where he knows it means something else. The authors he cites, who are also his co-authors, had no problem making this clear for their readers in philosophy.

Dawid recycles this definition in a later paper and again ties it to ordinary Bayesians by rewriting Bayes’ theorem:

Somehow dividing both sides by P(T) means Bayes’ theorem “implies that data E confirms H if P(E|T) > P(E).” This is algebraically equivalent to the definition for the word “confirms” above, except he drops the “if and only if.”

Confirmation, as before, can occur even if P(T|E) is near zero, which means that a theory is not worth the paper it’s printed on.

But this is just evidence that Dawid knows he’s guilty. The evidence against the formulation itself is simple. The fact that P(T|E) > P(T) is not confirmation is self-evident. It means you can confirm the moon is made of cheese by its color. The definition is so extreme it is the basis for the famous Raven Paradox. Dawid doesn’t cite this or any other dissent.

Furthermore, ordinary Bayesians would say that if you put one of the 10500 versions of string theory into Bayes’ theorem, you get something like 1/10500, or zero, plus or minus some evidence of which there is almost none. At a conference organized to debate the “confirms” paper, Dawid himself said there is none. According to Bayes’ theorem, zero is a very good estimate.

Benefit of the Doubt

Let’s make a strong case for Dawid, though, and say all he is guilty of is endorsing an extreme form of cherry-picking. Any evidence you can find for something does technically increase the odds it’s true. One has to admit that other evidence may decrease it, but so what? It doesn’t matter if he’s used a word confirmation that might look good on a grant application or in a newspaper. He’s guilty of fighting for his side with a little wordplay. Let’s also suppose this society we’re so afraid of poisoning can survive extreme cherry-picking and claiming any evidence as confirmation. (It can’t.)

The really egregious part is that the point of Dawid appealing to the power of evidence is to ditch evidence. This is just one paper in his careerlong argument for non-empirical confirmation: You can accept your theory on the thinnest possible evidence. If you can’t find any evidence at all, that’s fine too.

In a later paper, Dawid cites his own work to endorse “arguments that resemble empirical confirmation.” (For logicians, an argument that resembles confirmation but isn’t confirmation can’t raise the probability that a theory is true according to that if-and-only-if Dawid left out.)

The Warnings

George Ellis, one of the world’s most prominent physicists, warned against Dawid in 2014. His and other non-empirical ideas were called the “most dangerous ideas in science” at the time. Here’s Ellis at that conference doing all that you can do sometimes:

After the conference, Ellis claimed the same victory, saying that string theorists had admitted that the theory wasn’t “’confirmed’ in the sense of being verified.” Two years later, Dawid responded in the literature, stating conclusively that there’s an “unfortunate mismatch” in the way the term is used in philosophy compared to physics, which may lead to some misunderstanding.

The Future

None of this stopped the paper from being cited. The “no alternatives argument” is still being used today, ironically to show that there isn’t a crisis and the critics are just sore losers.

Sour grapes, as Professor Dave would say.

There’s a much larger audience on YouTube than Physics World could dream of, where Professor Dave defends string theory as empirical. He might be benefiting from the superweapon unwittingly, who knows. But he seems to think the issue is as serious as it gets. The question is whether or not he can be convinced that he’s the one with the bomb.

This was, I now realize, an unfortunate saga in which I participated by emailing the editor and asking for a response to the review from an empiricist. Physics World has updated the review by linking to a response from Grimstrup and making (undocumented) changes to the text. That said, I think the Grimstrup post is thin-skinned to the point of censoriousness. In my opinion, everyone lost sight of the stakes involved.

Professor Dave was enjoyable when he was going after flat earthers and creationists. It was not easy tbh. I wonder if we got used to having antiscientific morons as opponents and he just imported that attitude.

This sounds exactly like the hard sciences' version of critical theory... We are living in a time of such anti-empiricism that contrary evidence is now labelled "epistemic violence".

There is simply too many people scrambling for too few tenures and this has produced a generation of thinkers manufacturing "knowledge" just to look like they are actually being productive.