Psychologists think there's a crisis in psychology

Results from a new poll

Metascience principles are now law in the United States. The law drew protests from the field, but metascience is undoubtedly influential, and it has the largest purview of any scientific field. Yet the huge questions metascience needs to answer have been left to a few scattered groups.

Two of these questions in psychology were probed in 2016 and never repeated in such an explicit way since: “Are we in a replication crisis?” and “If so, why?”1

Spencer Greenberg’s group at Clearer Thinking published results of a survey a few weeks ago that helps to end this drought and may help us know if anything is working. They asked psychologists if psychology is still in crisis and why.

Clearer Thinking has been picking up academia’s slack in several ways, notably rapid replication, and proposing solutions and hypotheses too impolite towards academics to have come out of academia. These are not outlandish or overly insulting ideas. For instance, the proposal that scientific reforms might act as patches to a leaky pipe that causes greater pressure on other cracks, or that replications should be done soon after publication to incentivize researchers to practice greater rigor. These are good ideas but they are too impolite. That is the background on Clearer Thinking, and academia lobbing itself softballs happens to be the whole problem in a nutshell.

The problem with Clearer Thinking is they are still a little bit polite, which I hope to correct here.

Are we in a crisis?

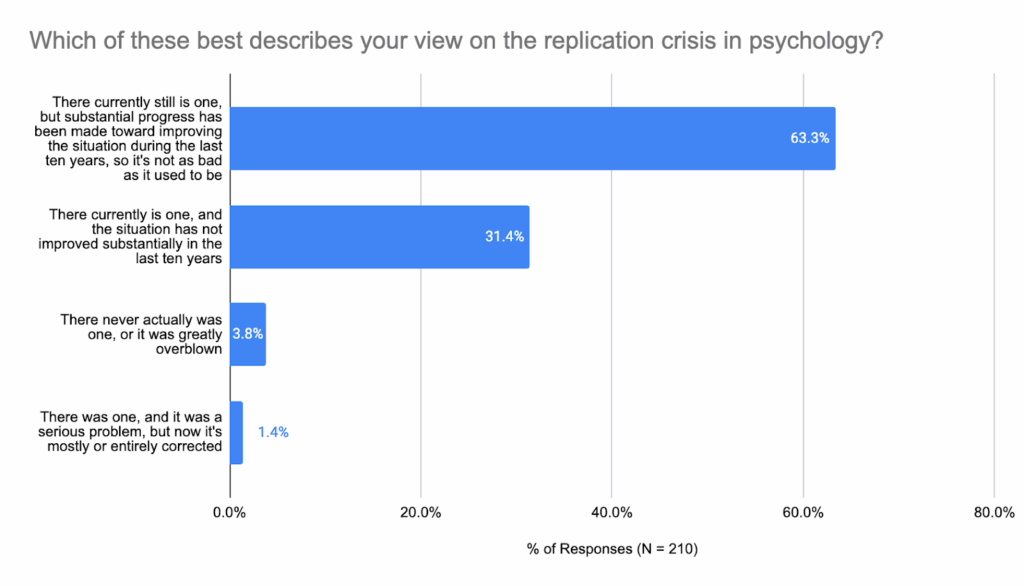

The poll almost perfectly agrees with Monya Baker’s 2016 poll in Nature, except most respondents now say “substantial progress has been made.” Baker’s poll found 90% of researchers believed there was a reproducibility crisis in science, and 52% said it was significant. The psychologists in the poll agreed (n = 44) at a slightly higher rate. In other words, 93% of psychologists would have used the word “crisis” then, and 95% would use it now except that most now believe a lot of progress has been made nonetheless.

What are we doing about the crisis?

The poll asks what improvements participants have made in their own research, and the ones who have made changes generally adopted preregistration (61%). So if we’re looking for progress, the best place to start might be preregistration.

As the survey suggests, preregistration is a clear and obvious winner among scientific reforms. It addresses base rate neglect, p-hacking, HARKing, and publication bias. Preregistration is backed by 2,000 years of thought on post hoc reasoning. It’s backed by statistics and something better than statistics: logic. Preregistration is already part of what protects us from dangerous drugs and medical devices. However, if preregistration adoption is the significant progress these psychologists are citing, it has not shown up in any studies of the literature.

The percentage of papers in psychology that are preregistered was measured in the early 2010s and again in 2022 and it rose from 2% to 7%. This is significant when you consider the intransigence of scientific practice and its size, the billions of dollars wrapped up in publishing and so on. However, a 5% increase doesn’t substantially move the replication rate.2

Much more importantly, the slow adoption of preregistration shows what type of problem scientific reform is. It shows 21st century reform isn’t the kind of thing that just catches on.

Compare preregistration with a practice that slightly increases one’s chances of publication, the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure, which has been cited 120,000 times. There are no non-profits set up to encourage use of the Benjamini-Hochberg over the less forgiving Bonferroni. Adoption happened automatically. 21st century reforms are not like this. They’re spinach, not ice cream.

One of the most important questions in the epistemic life of Earth’s 8 billion people is: Are scientists going to adopt reform or are they going to resist? This is the question we need answered. We need to interpret what a 5% increase in adoption — maybe 6 or 7% by now — means.

Change that reduces publication, even in metascience’s home turf of psychology, is spinach. We know it is. Even the small amount of progress is among self-selected adopters. They could be the ones who can afford to preregister. Their work is more certain to start with. Their subfield is more vague. Their job less in doubt. It moves the needle of discovery much less than its own prevalence might suggest, and it doesn’t predict future adoption.

The status of p-hacking in 2025

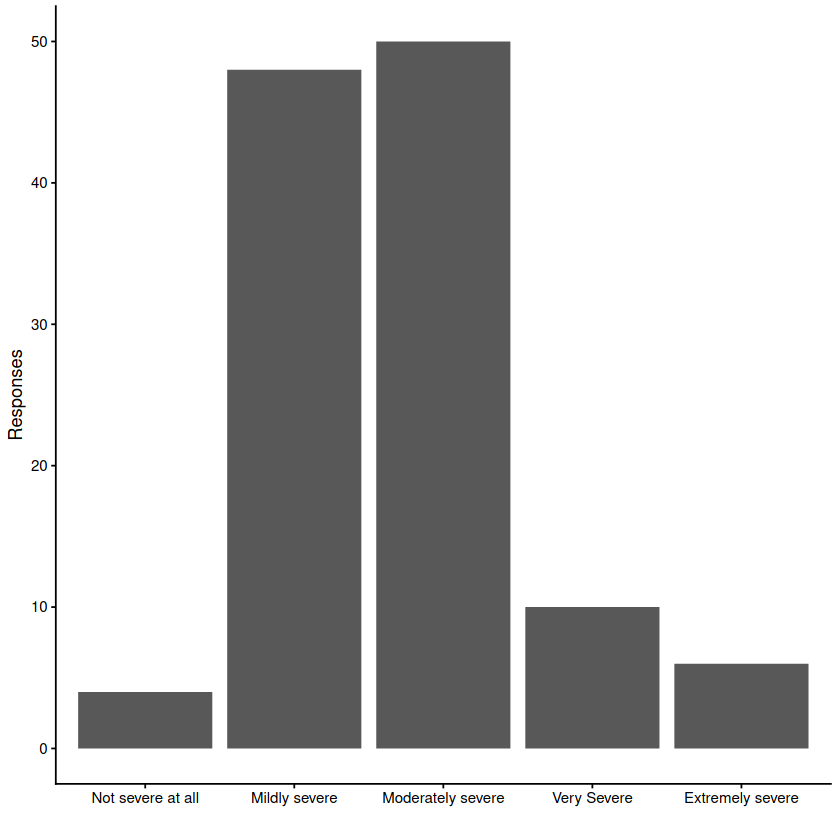

The survey asked how serious p-hacking is at the top 5 psychology journals. The results look like this:

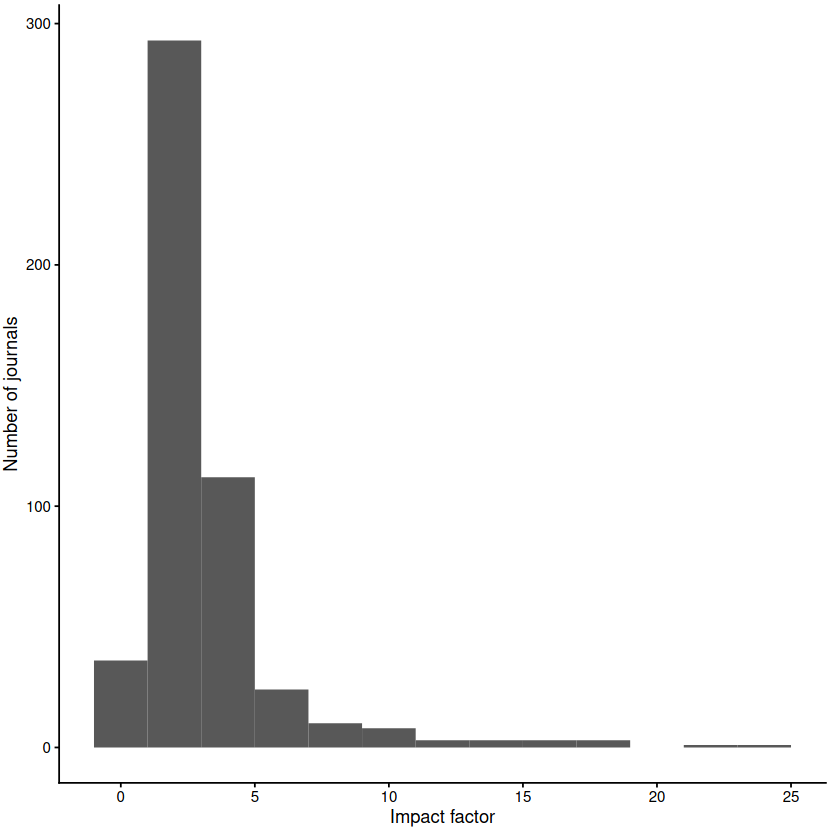

To put “top 5” in perspective, the top journals occupy a hierarchy that is shaped like other highly competitive environments:

Only a few are elite and many exponentially less so. Impact factor is not a good measure but it does measure influence. If p-hacking is a problem in the elite, its findings are at least influential there. It also stands to reason that it’s probably a problem everywhere.

Why do researchers bend the rules?

Famously, early reformers in psychology blamed the unconscious and forgetfulness. Feynman blamed “fooling yourself.” These charitable explanations are certainly partially true but they are starting to lose steam as predictors. If being charitable was supposed to be a catalyst, it is failing at that too.

In the free-form responses to the “reforms adopted” question, nobody mentioned combating their unconscious or forgetfulness because nobody believes those hypotheses. Nobody has bothered to find out if they are correct because they’re obviously not. A better predictor consistent with available evidence is Darwinian: Academics are p-hacking for survival in their profession and in their life’s work. They are doing so most likely on purpose or in deep denial. If they didn’t bend the rules, they might not have a job and all their friends, loved ones, and the rest of science would blithely continue on without them, winning Nobel prizes, educating students, and truly discovering some things. Discovering less maybe, but it’s the price of survival.

The replication rate

In another indication that 95% of psychologists are right that there still is a slight crisis, participants guessed the replication rate for the top 5 psychology journals and the average guess was 55%. We’re used to this ≈50% metric now, but in 2005 it was shocking. After all of this progress, the participants’ favorite journals are still only around a coin flip. Hopefully progress is not just inuring us to the numbers.

One optimistic way to interpret the higher adoption of reforms in some top journals (as high as 58% by one count) is to say that true discoveries will come out of better journals. The total replication rate doesn’t matter as long as some good work has been done and it shades out the rest. This is truly hopeful and it is possible. Unfortunately, the data didn’t indicate elite work either. Respondents were asked which findings have held up over the last 15 years. Other than a small cluster who said metascience, and a larger one who said there aren’t any, every answer was different.

Responses:

There’s much more in the data and Greenberg says there will be more analyses in the next few months. Announcements of new posts come through their newsletter. Their post was by Director of Replications Amanda Metskas. I clarified the replication estimates came from participants after a review by Clearer Thinking.

Both Baker and Clearer Thinking shared data. The code for this post is here.

For a similar poll in biomedicine, see Cobey et al., 2024.

The Registered Report format is less hackable than preregistration and arguably more supportive to researchers’ careers. Its prevalence is around 2.7% in its best year (2023) despite near unanimous endorsement in the community and among community leaders.

In their follow-up paper where they looked at 12 randomly selected recent publications, they found no p-hacking and an 83% replication rate. But obviously that's a very small sample, and they did find some other worrying methodological problems that are less widely discussed.

Great article. I think the change to require preregistration (or at least normalize it as the standard but allow justified exceptions) has to come from journals (through submission requirements) and universities (in annual performance evaluations).

Preregistration should reasonably protect against things like p-value hacking, but I realized recently to my dismay that they can still leave lots of room for other biases (e.g. confirmation bias of pet theories) unless the researcher is really diligent about designing their preregistration to test competing theories against each other.

I wrote about an example recently in my field, but to put it in general terms, the preregistration simply says "we expect to find an association between A and B in observational data" and claim support for their pet causal theory, while ignoring competing explanations (including reverse-causal ones). This is almost a worse situation because authors can claim their preregistered hypotheses were supported, when the results really don't advance our understanding in a meaningful way.

https://arielleselyaphd.substack.com/p/pre-registration-of-research-plans?r=45yctx

Edit to add: I still support preregistration, of course - it's a big step in the right direction. We just have to be mindful of its limitations and what other good practices would help (e.g., adversarial collaborations which would be better at testing competing theories).